I am the voice inside your head

(and I control you!)

It’s not every day we get to celebrate classic albums but this one, well, Nine Inch Nails’ The Downward Spiral, changed my life. It had an impact. It moved me. And here we are two decades later, and it still has the same effect.

And I know I am not alone on that score.

Simply put, it is a masterpiece. A visceral exploration of a protagonist losing his mind, his soul and ultimately his very life.

I am the lover in your bed

(and I control you!)

How the creative process of the production of this album did not claim lives throughout is a mystery. People should have died whilst this was being created I can assure you. With the studio inhabited and visited by members of the Jim Rose Circus and Marilyn Manson – the levels of debauchery, misadventure and illicit substances were at a rampant high.

I am the sex that you provide

(and I control you)

It was recorded in an actual house of death. Horrific death. 10050 Cielo Drive, Benedict Canyon, Los Angeles where the Manson gang murdered and mutilated Sharon Tate and her unborn child. Pause. Think about that for a second or two.

Yet this was the location of Reznor’s studio. From hell, came art.

And you can get a glimpse of what the house looked like in Tarantino’s latest offering, or Nine Inch Nails’ Gave Up video which was filmed inside.

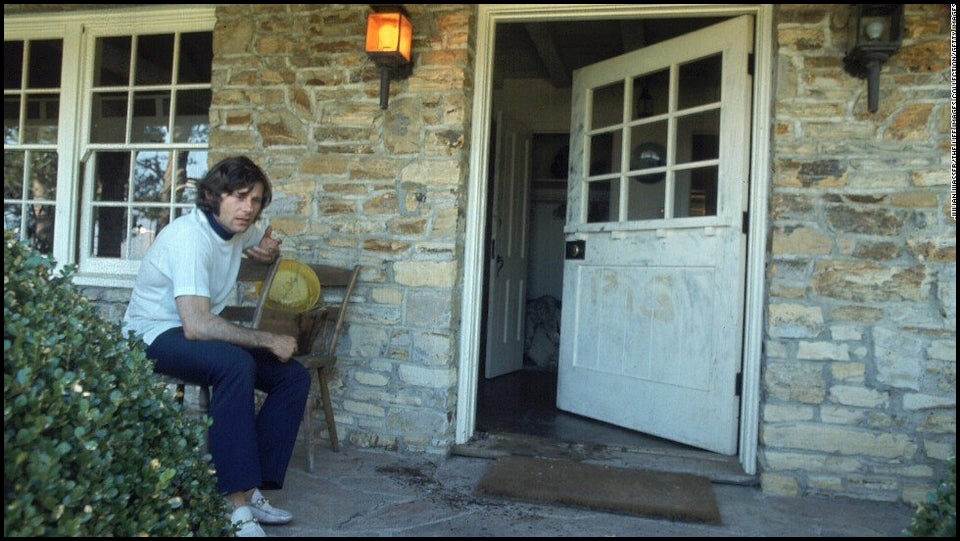

The Tate Mansion

August of 1969. Roman Polanski sitting outside his house after his 8 1/2 months pregnant wife Sharon Tate was brutally killed by the Manson Family. Notice the word PIG written in blood on the door that Trent Reznor bought and had in his studio in New Orleans.

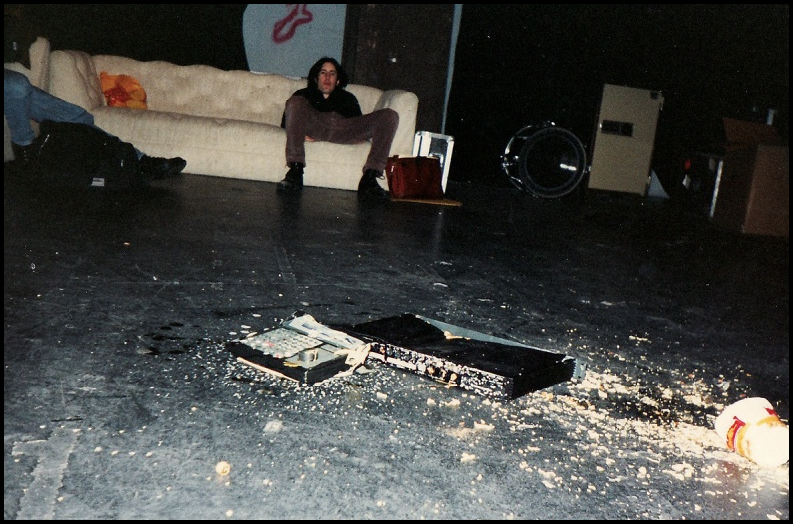

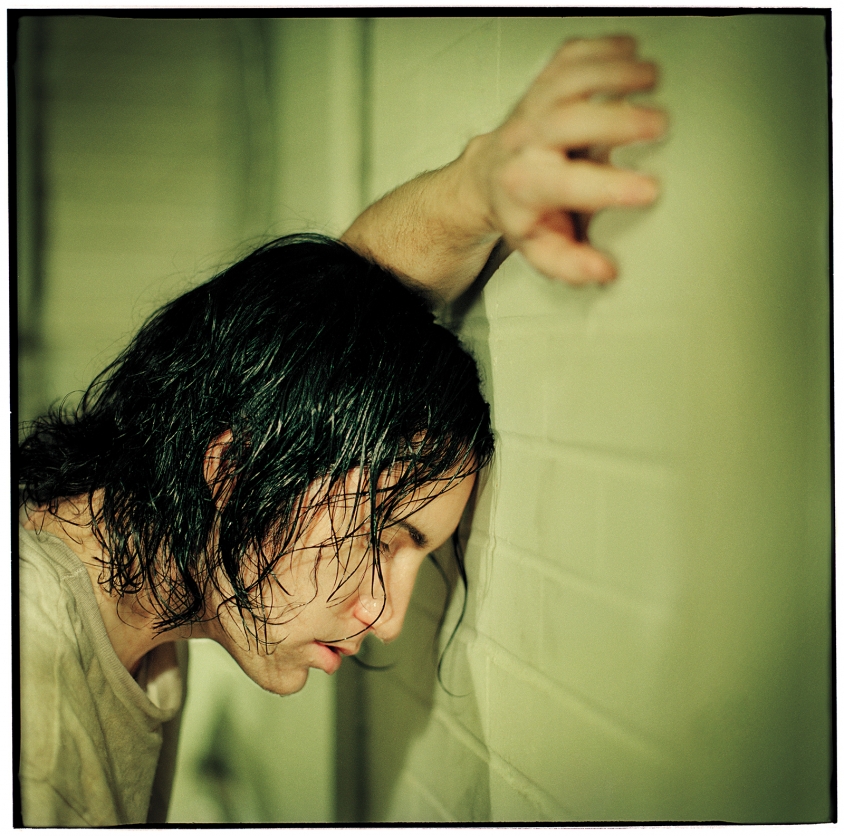

1994 Trent Reznor inside the Tate Mansion where Broken and The Downward Spiral were recorded.

“While I was working on Downward Spiral, I was living in the house where Sharon Tate was killed. Then one day I met her sister. It was a random thing, just a brief encounter. And she said: ‘Are you exploiting my sister’s death by living in her house?’ For the first time, the whole thing kind of slapped me in the face. I said, ‘No, it’s just sort of my own interest in American folklore. I’m in this place where a weird part of history occurred.’ I guess it never really struck me before, but it did then. She lost her sister from a senseless, ignorant situation that I don’t want to support. When she was talking to me, I realized for the first time, ‘What if it was my sister?’ I thought, ‘Fuck Charlie Manson.’ I went home and cried that night. It made me see there’s another side to things, you know?” — Trent Reznor

1994: Reznor’s studio set-up within the Tate Mansion.

Order Definitive Edition The Downward Spiral here…

https://www.ruemorguerecords.com/product/nine-inch-nails-the-downward-spiral-definitive-edition-2lp/

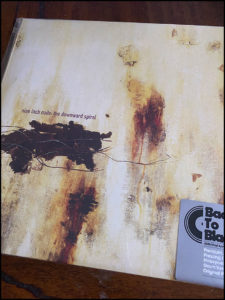

The Downward Spiral still stands as one of the greatest albums ever recorded. Ever. It remains as one of my most favourite albums of all time and trust me, I have heard many.

It is a living testimony to the darkest corners of one’s mind. It is a slab of literal musical depression and it will take you to many, many unfavourable places if you dare listen to it deeply from start to finish.

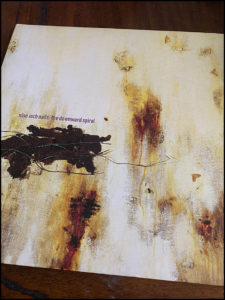

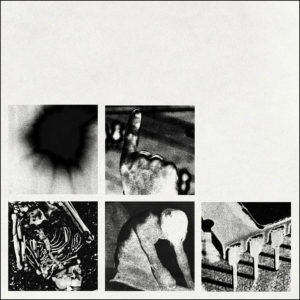

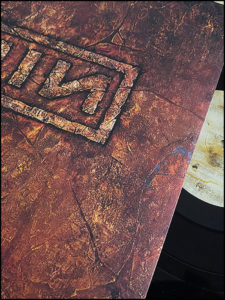

The Story Behind The Cover Art

Revolver Magazine 2010

When Trent Reznor contacted British collagist Russell Mills in 1994 about creating a cover for The Downward Spiral, the second album by his group Nine Inch Nails (who recently retired from playing live concerts), he had a list of words he wanted the art to evoke. Chief among them were “attrition,” “wound,” and “decay”—ideas the industrial rocker felt lurked beneath the “sheen of America’s contemporary, highly glossed society,” as Mills puts it. After being promised that the typography would be minimal, Mills says, “It seemed like a dream commission, as I was essentially being asked to produce the kinds of works that I would be doing anyhow.”

Asked to create art for a bevy of items related to the album—the jewel case J-card, booklet, singles (“March of the Pigs” and “Closer to God”), and more—Mills ended up preparing 25 mixed media pieces for Reznor’s consideration. Partway along, designer Gary Talpas told him he needed something for a slipcase, too. “It made little difference to my working process,” Mills recalls. “I’d already identified the piece that I felt and hoped would be used as the front cover, which I was referring to as ‘Wound.’ Luckily I was right and ‘Wound’ was used on the slipcase cover, the ‘shop window.'” Throughout most of the process, Mills hadn’t even heard a note of music. When he finally got some songs, they only confirmed he was in the “right territory.”

About what became the cover, Mills says, “I had been thinking about making works that dealt with layers—physically, materially, and conceptually. Given the nature of the lyrics and the power of the music I was working with, I felt justified in attempting to make works that alluded to the apparently contradictory imagery of pain and healing. I wanted to make beautiful surfaces that partially revealed the visceral rawness of open wounds beneath.”

Consisting of a two-foot square wooden panel slathered in plaster, oils, acrylics, rusted metals, dead insects, wax, varnishes, blood (Mills’ own), and surgical bandaging, “Wound” took about two weeks to complete.

“Physically, it’s sinewy and visceral, like the music,” Mills says of the finished product. “I’d love to be doing more of this kind of work, especially for Nine Inch Nails, as my work seems like an ideal visual mirror for their music and for Trent’s ideas.”

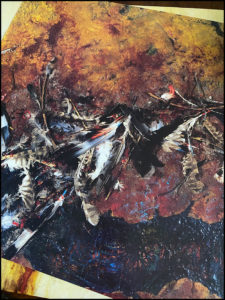

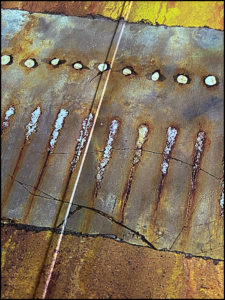

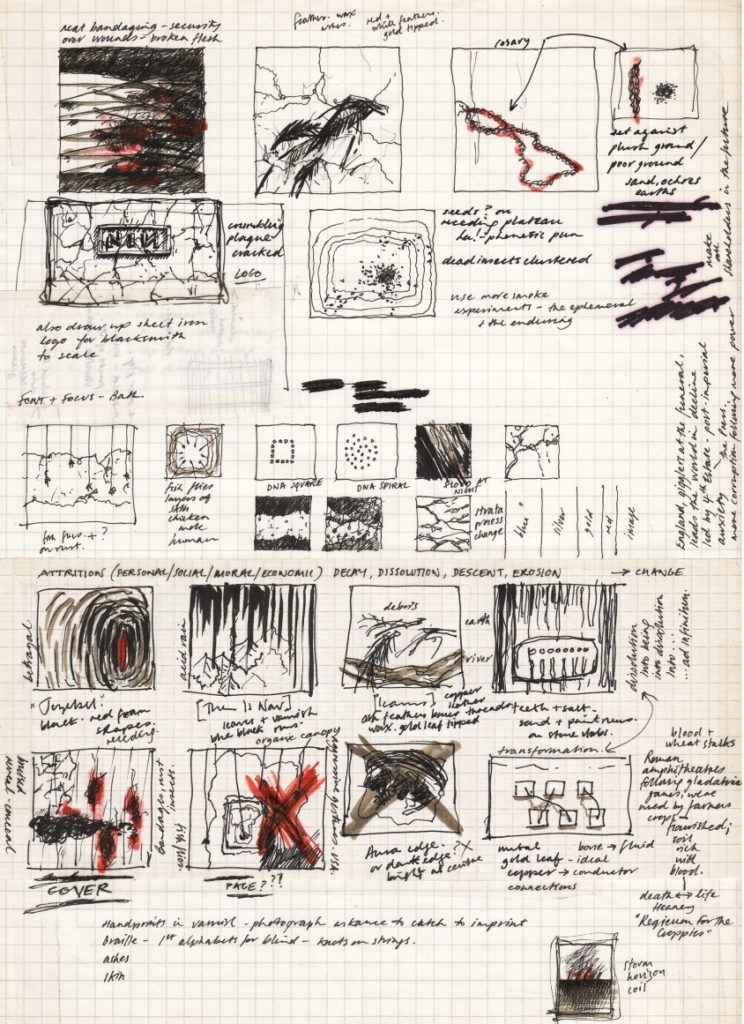

Artwork by Russell Mills created around The Downward Spiral Theme

Russell Mills On… Meeting Trent Reznor and His Haunting Nine Inch Nails Artwork

Words Russell Mills

In 1994 I was living on a back road just outside of Ambleside in the Lake District, Cumbria. My home was a wonderful old house made up of two conjoined houses: the earliest, a 17th century farmhouse and the latter, a Victorian addition of 1841. My studio was in a 17th century barn next to a stream. It was formerly the home of Dora Wordsworth—Wordsworth’s favorite daughter—and her family. The house was visited by Wordsworth, his family, and all the Romantic poets. Neighbors had included Thomas and Matthew Arnold, Thomas De Quincey (he wrote Confessions of an English Opium Eaterin Fox Ghyll, the house next door), various members of the Wordsworth family, and every so often Woodrow Wilson who would come to visit in secret, staying at a cottage a few hundred yards down the road. The road itself, known as Under Loughrigg, was and is recognized as one of the most beautiful walks in the Lake District, had been walked by a galaxy of cultural stars, thinkers and visionaries, including Wordsworth, Coleridge, Southey, Tennyson, De Quincey and one of my ultimate heroes Kurt Schwitters, amongst many others.

At that point I was in the middle of working on a year-long commission for the Royal Shakespeare Company, producing artwork for use in all of their print campaigns (posters, programs, flyers, etc.) at their three venues in Stratford-upon-Avon, Newcastle, and London. One beautiful spring morning I was outside in the garden taking a break, having a coffee, and reading the paper. The view I had was over fields to the River Rothay, across the valley down to the little town of Ambleside with its church steeple and irregular clusters of roofs set against the range of fells called Wansfell. My neighboring farmer was out with his Border Collies rounding up the sheep. It was an idyllic, bucolic, rural, very typical reassuring English view; very old world.

The phone rang. It was Trent Reznor’s then manager, who having introduced himself, then introduced his then-designer Gary Talpas, and finally Trent himself. His manager was on one phone in Cleveland, Gary on another, also in Cleveland, and Trent was on another phone, possibly in LA. It was my first experience of a conference call and given the context of where I was, what I was looking at, and the project I was currently busy with, it seemed fairly surreal. They explained that Nine Inch Nails were preparing a new album; they’d seen my work and liked it very much and they asked whether I’d be interested and able to undertake artwork for this forthcoming album—The Downward Spiral. I told them that I knew NIN’s work and was a great admirer, and that, yes of course I’d be very interested in taking on the commission. Having got over the preliminaries Trent and I talked for about 20 minutes about ideas and possible directions. I came off the phone already knowing the kind of territory that I thought I should explore and I began work that afternoon.

Two days later his manager called again. He said that Trent doesn’t work with people he hasn’t met and that I was to go to Manchester Airport (my nearest airport) on such and such a day, fly to LA to meet Trent. Two days later I was in LA. I was met by Gary who took me to book into my hotel, the Hotel Mondrian on Sunset Boulevard—”a parallel universe of perpetual possibility”. My room was the penthouse, a huge suite on the top floor, big enough for several large families, with views over LA and the hills. I had one backpack with me.

He then took me for a quick tour of some of the beaches. It was drizzling rain, grey, bleak and the beaches were empty. I wasn’t too impressed or interested. That evening: dinner with Trent, Gary and the other members of NIN in the hotel restaurant. We talked more about the ideas we’d already discussed on the phone a few days earlier, bringing them into sharper focus. Trent didn’t talk much, he let me talk while he stared at me, as if he was checking me out. The other members of the band were charming, occasionally entering into the conversation, but mainly talking between themselves. It was all very low key. After a couple of hours Trent and co. left, leaving Gary and I to talk over a drink. Gary then left as he had to drive back to Cleveland.

I was alone in a city I had no knowledge of, I didn’t know anyone there, and I was due to fly back to the UK the next day. I was considering venturing out to wander, look around, sniff out the area, possibly find a bar, when out of the shadows of the restaurant a figure I vaguely recognized emerged. It was the Irish singer and musician Gavin Friday. I’d met Gavin several times in Dublin and London, usually in the company of an old friend the Edge of U2, who I’d first met in 1984 at Slane Castle when they were recording The Unforgettable Fire with another of my old friends, Eno.

We headed for the bar. He had been in LA working on some soundtrack work for a few weeks and was bored out of his skull and incredibly frustrated with the place and the people. He told me he’d been spending every day working and having to deal with people, well arseholes, who were constantly wanting to change what he was trying to do. He was desperate for intelligent conversation—for English/Irish conversation—about art, politics, culture, music, films, humor. We talked about everything and anything well into the morning and got fantastically drunk. I think it was about 4:00 a.m. when we staggered up to our rooms, giggling uncontrollably. On the occasions since when we’ve met he has always given me a huge hug and thanked me for being their that night. I reciprocate as I think that fortuitous meeting saved us both that night.

I returned home and just got on with the work, becoming totally immersed in the project, eventually producing about 30 new mixed media works towards uses on what became The Downward Spiral album. Other commissions followed every so often: Further Down the Spiral, March of the Pigs, Closure, etc.

Unused logo concepts

The Downward Spiral Era intimate photos by Joseph Cultice

Versions

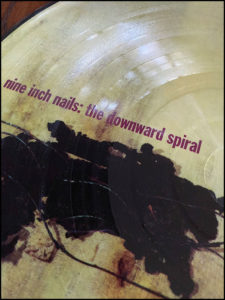

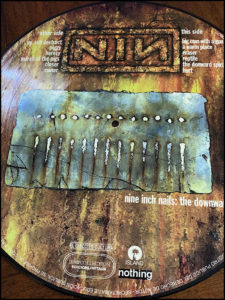

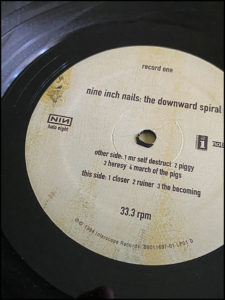

The Downward Spiral:

Picture Disc version. Have never bothered playing this. Pretty sure it’s nothing official or sanctioned by the NIN camp. One for completists.

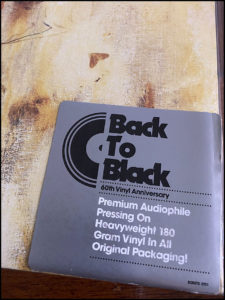

The Downward Spiral:

Back To Back Audiophile Series: I’ve heard this one was also not endorsed by the NIN camp. Released in 2008 it is a faithful reproduction of the original pressings with all art, labels etc

The Downward Spiral:

UK First Pressing (1994): stunned to find this one out in the wild. Absolute mint condition throughout which I managed to grab for about $40AU.